“Transforming a Site of Sexual Exploitation to One Where People’s Rights Are Respected.” That is how the founders of Asociación Mundo Igualitario (Equal World Association, or AMI), an organisation in the city of Mar del Plata (Buenos Aires Province, Argentina) describes the new AMI Culture and Education Centre. This is an emblematic, transformational site, especially for the LGBTIQ+ community.

by Laura Gambale (*)

A breeze comes in through the open windows; pop music is playing somewhere in the back, maybe in the kitchen, where a group of women are cleaning. Each sips her own mate and we talk about the history of Asociación Mundo Igualitario (AMI) and the new centre, how AMI took over this property in a luxurious seaside neighbourhood and the group’s plans for the future.

WHAT IS AMI?

AMI is the brainchild of two members of the trans collective, Daniela Castro, a Mar del Plata city councilperson, and Cintia Pili, a recognised activist and advocate for LGBTIQ+ rights. It was started on July 15, 2014. A short time later, the organisation’s current president, Claudia Vega, came on board, along with vice-president Agustina Ponce and secretary Patricia Vozzi. The group currently has 40 members, most activists in different social spheres. At AMI, they have joined forces to defend the rights of historically marginalised communities, like the city’s transgender/travesti community.

“AMI originated from a need to build opportunities for advocacy that have a pluralist focus and a multidisciplinary, intercultural approach. It deals with defending identity; self-determination; and the real participation of gender-diverse people in spheres of power, decision-making, projects, discussion and debate, but also in their execution and implementation,” explain the founders.

THE PANDEMIC AND THE NEED FOR A MEETING PLACE

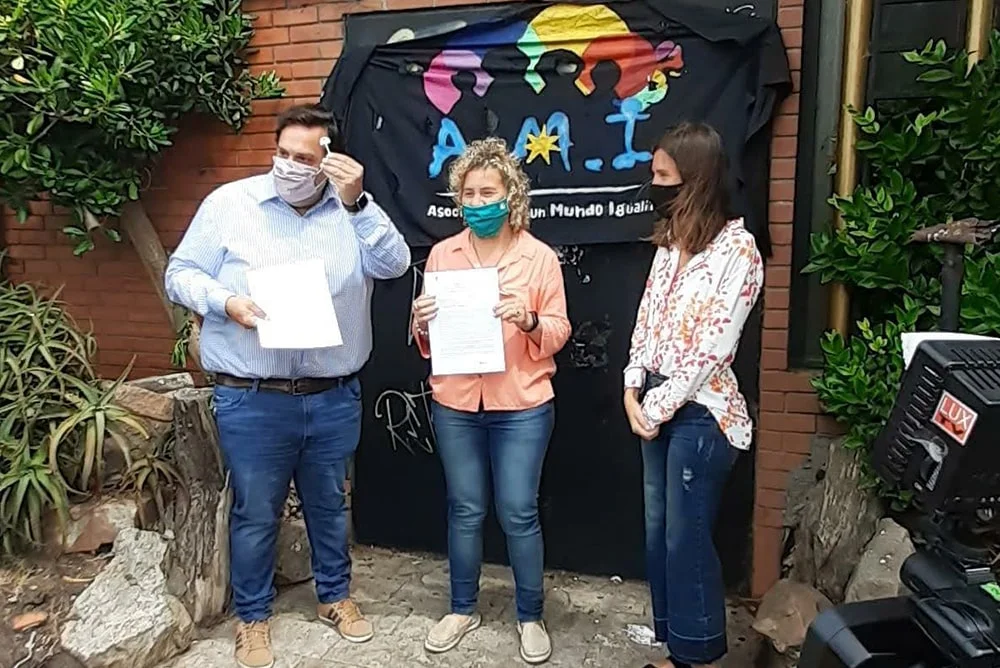

In January of this year, a court passed down a historic ruling: AMI was given custody of the former VIP brothel Madaho’s. By assigning custody to the group, which works to end human trafficking and gender discrimination, AMI would be able to repurpose the site into its headquarters.

AMI president Claudia Vega, who is an attorney, a biodance facilitator and biocentric educator, explains, “During the pandemic, there were even more infringements on the rights of a collective [the LGBTIQ+ community] that has always had to struggle to survive. That was why it was so important to have a space of our own where we could do our work and people could come to us.”

In the city of Mar del Plata, AMI and other local organisations put together the first emergency LGBTIQ+ committee during the months when lockdown measures were most extreme. The committee worked to ensure that vulnerable individuals had food and basic household goods.

“We knew that sex workers could not leave their homes and their needs were dire so we began delivering bags of food, using our own vehicles. The transgender/travesti community was one of the hardest hit by the pandemic; many had nothing to eat,” explains Vozzi.

Vega adds, “For many years, we’ve taken a territorial approach to our activism that proved particularly useful for dealing with this wholly new issue the community was facing.”

HOW AMI GAINED CUSTODY OF THE FORMER VIP BROTHEL

In January 2021, when the risks associated with COVID-19 remained high, the AMI group was assigned guardianship over Madaho’s. The former VIP brothel, located in one of the city’s poshest neighbourhoods, opened in April 2007 and closed in September 2014.

At that time, the courts shut down the brothel as part of a case in which it was determined (in 2020) that the owners of Madaho’s were guilty of sexual exploitation of the brothel’s workers. At the same time, a second case on money laundering is working its way through the federal courts. In January of this year, as both cases continue, federal judge Santiago Inchausti ruled in favour of a request by the State Asset Administration Agency (AABE) to embargo the property and the AMI was granted custody.

Vega remembers that when they learned of the lawsuit and the possibility of the organisation being entrusted with the building, they drafted a petition that was signed by 22 city organisations and presented it in court in November 2020. The petition describes AMI’s work to defend the rights of the LGBTIQ+ community. “After we delivered the petition, Pato, Agus and I stopped by the former brothel and laid our hands on the door to transmit positive energy. We believe in things like that,” she adds.

The court ruling on the custody specifies that the organisation entrusted with the building must not only restore it, but also do outreach work aimed at ending sexual trafficking and exploitation.

When the AMI members found out the courts had granted them custody, they agreed this was “an unprecedented ruling, one that contributes to building a gender and diversity perspective in the judicial branch.”

In Pili’s view, “accessing the building means having a place of our own for workshops, activities and work we had been doing in different places lent to us. We dreamed of having a place of our own and it finally happened.”

THE BEGINNING OF THE TRANSFORMATION

In summer 2021, the doors of the building—closed since the courts had ordered the shutdown years earlier—opened again. The stage was intact and frozen in time: cigarette butts in the ashtrays, boots left on a table, areas flooded from leaky pipes, glasses with drinks, mugs half filled with coffee, and trash strewn everywhere.

“We opened the doors for the first time on January 4th of this year, without a dime. All we had was our bodies and our will,” recounts Claudia with emotion. She pauses and then remembers “the enormous support we received from the organisations and the trade unions—both local and national—when word got out that we had been granted custody of the building.” “For us, that support was key. They sent donations, money and even people hours and time to transform this misogynistic, elitist space,” Claudia concludes.

At the beginning of the year. AMI reached out to architect Alejandra Urdampilleta to discuss redoing the interiors and making the space usable as soon as possible. The architect was so excited about the project that she came on board right away.

“Working with the architect, we laid out our priorities and determined what could wait for a second stage,” explains Claudia. At that point, they consulted with Fondo de Mujeres del Sur (FMS). AMI had been in touch with FMS the previous year to discuss the food and housing emergency facing the transgender/travesti collective during the country’s strict lockdown. AMI explained to FMS the plans to refashion the space and the resources they needed.

Vega explains that with the funding they received, they were able to redo the wiring; repair walls, ceilings and floors; fix water leaks; and install heating. In short, they made the space usable again.

TASK LISTS, WORK SHIFTS AND A CRITICAL MASS

AMI members and volunteers worked for eight months. Work started early in the morning and continued into the evening. “For the first month, the place smelled so bad that we did three-hour shifts to keep from vomiting. We put together task lists by groups, working to establish priorities and get them finished. We had to remove the mirrors covering the windows, do masonry in the bathroom, put in new floors, take down the carpeting that covered some of the walls and strip off the stainless steel covering the columns,” recalls Ponce.

“Everything we could do at no cost, we did. And for the rest, we hired construction workers. Some of the workers decided not to charge us when they found out about the project and others gave us a discounted rate,” she adds.

“Our guiding principle was to make this as sustainable as possible. So besides recycling all the materials we could, we also decided to install an eco-friendly electric system. We were on such a tight budget that before we threw anything away, we thought it over 70 times. We recovered everything that was recoverable. Even so, we filled ten large containers with garbage,” recalls Vega.

“This was a VIP brothel that was homophobic and transphobic, a place where wealthy, powerful men exploited young, vulnerable women. Travestis weren’t allowed in except once when Daniela Castro, one of the AMI founders, was called in to do a one-off job when she was still a sex worker,” adds Ponce.

Vozzi sums it up as follows: “This is a place that we transfeminists reopened for the public at large. We’ve been on the margins of society suffering discrimination for so long: now we want to be the ones to invite the community in.”

At the beginning of September, the ribbon was cut on the AMI Culture Centre. Members were thrilled to have transformed this place into a cultural, educational space where the community can learn about diversity and feminism. Workshops, psychological support and legal consulting are also provided by the AMI professionals.

One of the challenges for the future, says Pili, is ensuring free, public education. “At AMI, we are very clear on a public policy geared toward education. That is why we began offered a gender perspective certificate program that is free and open to the public.”

Cintia adds that they want to “train future trainers,” and that once students have finished their program, AMI will help them access formal employment. “We want to move away from welfare,” she declares.

A PIONEERING SCHOOL

Many AMI founders, most of whom are professionals or finishing up a degree in healthcare or the social sciences, are trained in biocentric education and biodance. With these tools, and with the support of the Argentine Ministry of Women, Gender and Diversity, the group launched the first certification program in gender and diversity. Classes in the “Love in Action” program are given at AMI’s new building. Vozzi explains the transformation as follows: “We are building a school in a territory that was ravaged by the patriarchy.”

“Biocentric education gives you the chance to change your way of communicating with the world. That’s why we say that this school can contribute to emotional relearning,” adds Vega. Combining virtual and in-person teaching, the school has 80 students in its first class.

“It’s shared learning. We are training activists in gender and diversity and also working on emotional reparations for many identities damaged by the patriarchy,” they add.

The AMI centre will also offer other activities for the whole community like workshops in biodance, tango and painting from a gender perspective. In addition, people can come in for psychological support, legal consultations and talks with social workers.

One area of the centre is dedicated to memory. It is a dark, narrow hallway covered with lipstick kisses where the women working at the brothel used to change before going on stage.

“Many of us were sex workers at one point. We understand that codes like these are about building a network, protecting and supporting others by leaving a mark,” explains Ponce.

Finally, university student and AMI member Guadalupe Bazán adds, “For us, the hard part is not only getting a job or beginning a degree program but sustaining it over time. Many of us don’t have mobile devices so this centre is going to allow many people to continue their studies or other activities, and even do therapy or get legal assistance. They’re going to be able to access internet, read, study and also get support.”

(*) Laura Gambale is a journalist who lives in Mar del Plata.

Some of the photographs used in this article were provided by AMI and others were taken by the journalist.